For those U.S. families whose breadwinners are still working and who didn’t lose their homes to foreclosure, etc., what we have been going through since the last half of George W. Bush’s administration mostly passes without personal pain. Small wonder then that the average citizen ignores the debates around economic policy, the safety net, and the nature and role of government itself; such matters are left to the special interests, the pundits, and, sadly, the talk radio and faux news show hosts.

Mrs. Pickett died a few years after we initially published her book. She was, as her memoir proves on every page, one of those spirits who make you feel more alive by knowing them. Though she was self-taught as a writer, she had a natural storytelling gift and the ability to express a scene so that you feel present in it.

Two or three of our young staffers and interns have remarked while copyediting and proofreading the page galleys of The Path Was Steep that it made them for the first time understand the Great Depression. Here’s an excerpt of a few pages from the memoir, in a chapter from the period when Mrs. Pickett’s husband David had found work in a West Virginia coal camp:

One afternoon, as we ate supper, a small boy and girl appeared at the kitchen door. The little girl was about ten and had a curious, old-woman look in her face. The boy, a year or so younger, stared at a plate of leftover boiled corn.

“Have you had supper?” I asked gently.

The girl’s face reddened. “We was just going to ask if you have any food to spare.”

“Of course there is food.” I took down two plates.

“Could we have it in a poke?”

“Are there others?” I asked.

“Mommie and Aunt Bess and three small children.”

“Where do you live?” I asked.

She bent her head, and her face reddened again. “Nowhere.” It was only a breath. “We—we’ve got people over the mountain.”

“Where did you sleep last night?” I put my arm around her shoulders.

“Down the road.” She raised her head. “I aim to pay for the food. I’ll wash dishes,” she said.

“You slept outdoors?”

“We built a fire. Hit wasn’t cold.”

Nights in the mountains were always cold. “Go tell your folks to come here for supper,” I said.

“If you’ll let me work. I aim to pay.”

“If that’s the way you want it,” I agreed. I knew the stern pride of the mountaineers.

“That’s the way hit has to be,” she said.

I stirred the fire in the kitchen stove, sliced salt pork, put it in a pan at the back of the stove, and ran to the garden. The pork just needed turning when I returned with corn, tomatoes, onions, and lettuce. By the time the corn bubbled on the stove in salted water, with a little butter added for flavor, and biscuits were browned, the girl was back with her family. The women, young and fair, looked tired and hopeless. The smaller children were shy, hardly speaking. After supper they were all a little more cheerful.

The girl’s name was Irene. She washed her hands, cleared the table, and began to wash dishes. One look at her face, and I didn’t interfere.

“You got some soap we could have?” her mother asked. “We ain’t washed no clothes since we left Pennsylvania.”

“How did you travel?” I took a bar of Octagon laundry soap from a pantry shelf.

“Rode a freight. They found us at the state line and throwed us off the train. Said if hit wasn’t fer the children, they’d a throwed us in jail.”

Irene swept the kitchen floor, then carried water to wash the clothes. They hung them up on my lines and stayed until dark; then the aunt said, “You mind if we sleep in yore yard?”

“We’ve plenty of room for all of you,” I said, my throat dry.

“Just make us a pallet,” she smiled listlessly.

But I crowded Sharon and Davene into bed with David and me, so the women could have a bed. Perhaps it was the first they’d slept in for many nights.

Irene spread their bedding on the floor. It was dirty and mud-stained. I offered my only clean sheets for cover. “I mean to pay,” her eyes were fierce gray. “I’ll sweep yore yard in the morning.” She had watched as I put the girls to bed, first kneeling with them for their prayers. She knelt and whispered, and I saw tears falling from her hands between her fingers.

I fought back tears. How had she kept her pride? Her mother, aunt, and the smaller ones had the very smell of the Depression about them. Pride, if they ever possessed it, and most mountaineers do, was gone and there was a trapped, animal look—I couldn’t describe it, but when David came in from work the next day, I knew. It was the look of cheap, shoddy, used goods.

There was two dollars in my purse. I didn’t even dare look at the fireplace, but slipped the money to Irene’s mother and gathered corn and tomatoes, found half a box of crackers and some cheese, and put them in a bag just before they left the next day.

Irene washed dishes, swept the floors, and was sweeping the yard when her mother called. “Time for us to git on.”

“I done what I could,” Irene told me.

“You did more than you should,” I stooped to kiss her.

She threw her arms around me and gave a big, gasping sob. “You are so good, as good as any angel,” she wept.

“Oh, no,” I whispered and held her close. “Why don’t you visit with us for a week or so?” I asked. I’d bathe the child, cut her hair, make her a dress. “All right?” I asked her mother.

“You can have her fer good if you want,” indifferently.

I looked at Irene, dreading to see the blow strike. But her eyes grew luminous and she ran to her mother. “I have to go with Mommie! I have to!” Her face grew protective, tender, burning with love, and suddenly I understood. The mother was whipped, cowed. Nothing was left to her, not even love for her children; but this child was not whipped. Somehow, Irene would get them through this Depression, if it ever ended, as a golden voice over our $14.50 portable radio promised over and over that it would end.

As they started away, Irene darted back to whisper fiercely, “Don’t think Mommie wants to give me away. She just wants to get a good home fer me.”

“Of course she does.” I kissed her, and her face lighted at my words. I offered them as a sacrifice to the child, and if He will accept a lie as a sacrifice, I offered them to God, for I knew the words to be a lie. Irene’s mother would be happy to be rid of the child. But no earthly power could make Irene believe this. Her love was so overwhelming that she wrapped it like a warm blanket around her mother. She was a swamp blossom. Pure gold, growing from black swamp mould. Perhaps her love would be strong enough to save her mother.

Sadly, there were not enough Sue Picketts in the 1930s to save or even help all the Irenes. But brick-by-brick, led by that golden voice that resonated on the Picketts’ $14 radio, Congress built the New Deal safety net programs, expanded during the 1960s by the Great Society legislation, that today by and large keep our Irenes fed, clothed, and housed during hard times. Today these programs are threatened. We should tread carefully before we dismantle them.

represent the 7th District of Alabama with fervor and dedication. Turner was born a slave and rose to be Alabama’s first African American representative in Congress. 140 years after Turner took office, Terri Sewell was put in charge of the 7th district, the first African American woman to do so. After the recent publication of The Slave Who Went to Congress—an illustrated children’s book detailing Turner’s early life and political career—Congresswoman Sewell visited Clark Elementary in Selma with authors Frye Gaillard and Marti Rosner and gifted students there fifty copies of the book. Sewell movingly told the schoolchildren attending her program that she “stands on the shoulders of Benjamin Sterling Turner,” who paved the way for her civil service with his bold

represent the 7th District of Alabama with fervor and dedication. Turner was born a slave and rose to be Alabama’s first African American representative in Congress. 140 years after Turner took office, Terri Sewell was put in charge of the 7th district, the first African American woman to do so. After the recent publication of The Slave Who Went to Congress—an illustrated children’s book detailing Turner’s early life and political career—Congresswoman Sewell visited Clark Elementary in Selma with authors Frye Gaillard and Marti Rosner and gifted students there fifty copies of the book. Sewell movingly told the schoolchildren attending her program that she “stands on the shoulders of Benjamin Sterling Turner,” who paved the way for her civil service with his bold choice to run for office. This incredible intersection of history reminds us of how important historymakers like Turner and Sewell are; the effects of their leadership can be felt in Dallas County today. The Slave Who Went to Congress—which the Midwest Book Review calls “a choice pick for personal, school, and library collections”—is a powerful account of an impactful life and, importantly, introduces Turner’s remarkable story of bravery and leadership to children around the world.

choice to run for office. This incredible intersection of history reminds us of how important historymakers like Turner and Sewell are; the effects of their leadership can be felt in Dallas County today. The Slave Who Went to Congress—which the Midwest Book Review calls “a choice pick for personal, school, and library collections”—is a powerful account of an impactful life and, importantly, introduces Turner’s remarkable story of bravery and leadership to children around the world.

project, with Brown directing and Lee signed on as executive producer; Brown has worked with Lee for more than 30 years, serving as editor on almost every film Lee has made. Brown met Bob Zellner twenty years ago and was fascinated by the civil rights activist’s story of redemption. He has adapted Zellner’s memoir into a biographical film, covering Zellner’s life from his time as a youth (he was born into a Klan family) to his becoming the first white field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The film features two rising stars in Lucas Till and Lucy Hale, both well-known for their roles in the hit TV shows MacGyver and Pretty Little Liars, respectively. Till plays Zellner with the passion and commitment to civil and human rights causes that the subject retains in his 80th year. To film one exciting scene, Brown and crew reenacted the tragic beating the Freedom Riders suffered in Montgomery outside of the actual Greyhound bus station where the historic event took place. Read more about Son of the South at the

project, with Brown directing and Lee signed on as executive producer; Brown has worked with Lee for more than 30 years, serving as editor on almost every film Lee has made. Brown met Bob Zellner twenty years ago and was fascinated by the civil rights activist’s story of redemption. He has adapted Zellner’s memoir into a biographical film, covering Zellner’s life from his time as a youth (he was born into a Klan family) to his becoming the first white field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The film features two rising stars in Lucas Till and Lucy Hale, both well-known for their roles in the hit TV shows MacGyver and Pretty Little Liars, respectively. Till plays Zellner with the passion and commitment to civil and human rights causes that the subject retains in his 80th year. To film one exciting scene, Brown and crew reenacted the tragic beating the Freedom Riders suffered in Montgomery outside of the actual Greyhound bus station where the historic event took place. Read more about Son of the South at the  with respect to the production of food. Foster started a gardening club a few years ago, talking to students about how one can grow a garden and helping them to see sustainability as a social justice issue. Following Booker T. Washington’s recent move to a new campus, he found himself with enough space outdoors for an official school garden. To continue his personal growth as a sustainability educator and advocate, Foster has joined forces with Loveless Academic Magnet English teacher Gina Aaij and will attend the Rob and Melani Walton National Sustainability Teachers’ Academy in Montana. “Since neither Gina nor I are science teachers, I thought we were a long shot to get in,” he said. Foster’s new book

with respect to the production of food. Foster started a gardening club a few years ago, talking to students about how one can grow a garden and helping them to see sustainability as a social justice issue. Following Booker T. Washington’s recent move to a new campus, he found himself with enough space outdoors for an official school garden. To continue his personal growth as a sustainability educator and advocate, Foster has joined forces with Loveless Academic Magnet English teacher Gina Aaij and will attend the Rob and Melani Walton National Sustainability Teachers’ Academy in Montana. “Since neither Gina nor I are science teachers, I thought we were a long shot to get in,” he said. Foster’s new book  Award in the Literary Arts. The award recognizes the demonstrated quality of her body of work, her contributions to the literary community, and the overall visibility she has helped bring to the arts. Pictured here with her daughter and son-in-law, Henderson is the award-winning author of several children’s books, but it’s her Eugene Allen Smith’s Alabama we are obviously most proud of. This book published by NewSouth Books is the definitive work on Alabama’s first state geologist, who spent the better part of a lifetime traversing the state with notebook and Brownie camera in hand, documenting Alabama’s abundant natural and geological resources. Smith’s work directly contributed to the commercial and industrial development of Alabama of the late nineteenth century. Lewis Dean in his foreword to the book says, “Smith was short in stature, but a giant of

Award in the Literary Arts. The award recognizes the demonstrated quality of her body of work, her contributions to the literary community, and the overall visibility she has helped bring to the arts. Pictured here with her daughter and son-in-law, Henderson is the award-winning author of several children’s books, but it’s her Eugene Allen Smith’s Alabama we are obviously most proud of. This book published by NewSouth Books is the definitive work on Alabama’s first state geologist, who spent the better part of a lifetime traversing the state with notebook and Brownie camera in hand, documenting Alabama’s abundant natural and geological resources. Smith’s work directly contributed to the commercial and industrial development of Alabama of the late nineteenth century. Lewis Dean in his foreword to the book says, “Smith was short in stature, but a giant of a man. He believed in progress. His life and work testify to the conviction that society and individuals can build a better world.” Like Smith, Ms. Henderson has done her state a service. Eugene Allen Smith’s Alabama reintroduces a preeminent Alabamian, who in his own time had a positive influence in shaping his native state and left an enduring legacy of science and service. We celebrate Ms. Henderson’s outstanding achievement in returning that story to us.

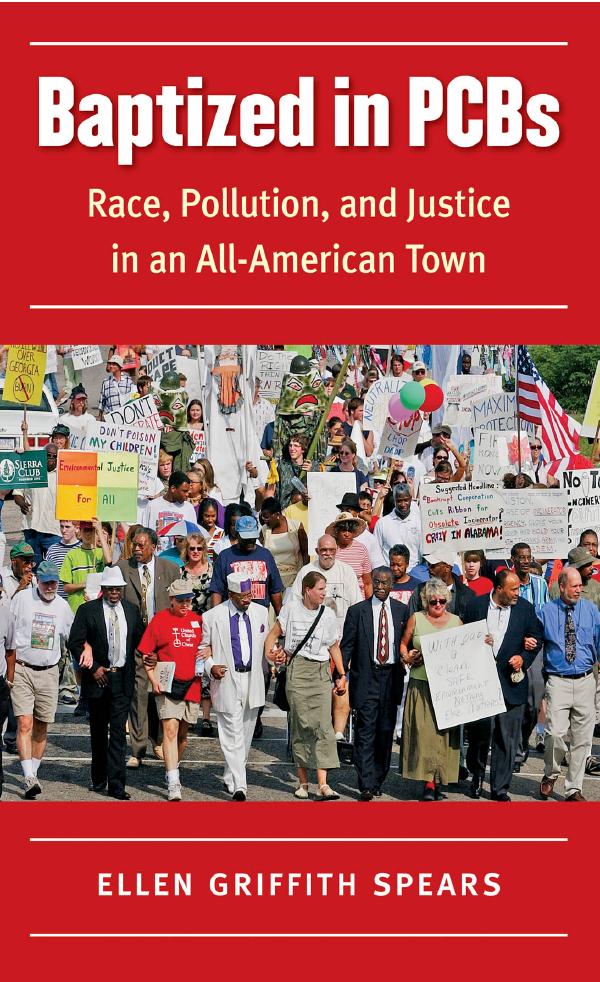

a man. He believed in progress. His life and work testify to the conviction that society and individuals can build a better world.” Like Smith, Ms. Henderson has done her state a service. Eugene Allen Smith’s Alabama reintroduces a preeminent Alabamian, who in his own time had a positive influence in shaping his native state and left an enduring legacy of science and service. We celebrate Ms. Henderson’s outstanding achievement in returning that story to us. Anniston, Alabama has a storied, sometimes infamous history, including the burning of a Freedom Riders bus in the 1960s and more recently, legal battles over environmental pollution caused by chemical plants in the city. A new book by University of Alabama professor Ellen Spears,

Anniston, Alabama has a storied, sometimes infamous history, including the burning of a Freedom Riders bus in the 1960s and more recently, legal battles over environmental pollution caused by chemical plants in the city. A new book by University of Alabama professor Ellen Spears,

In the current

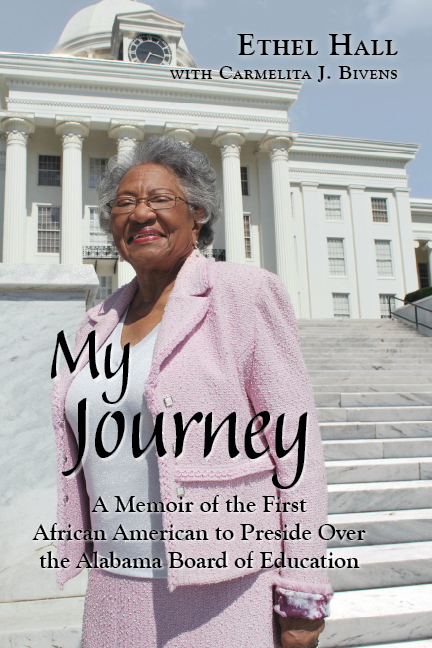

In the current  Dr. Ethel Hall, the first African American woman elected to the Alabama State Board of Education, died this month at age 83. Hall had recounted both her two decades on the Board of Education and her early struggle to achieve higher education in her memoir

Dr. Ethel Hall, the first African American woman elected to the Alabama State Board of Education, died this month at age 83. Hall had recounted both her two decades on the Board of Education and her early struggle to achieve higher education in her memoir