Knopf Editor Ashbel Green remembered by author Robert J. Norrell

Monday, September 24th, 2012 by Brian Seidman Robert J. Norrell, author of Eden Rise, sent this remembrance of former Alfred A. Knopf editor Ashbel Green:

Robert J. Norrell, author of Eden Rise, sent this remembrance of former Alfred A. Knopf editor Ashbel Green:

Ashbel Green accepted my dissertation for publication at Knopf six weeks after four professors at the University of Virginia in 1983 said the manuscript was worthy of the doctor of philosophy and not far from being ready for publication. Paul Gaston, my mentor, had unbounded confidence in his judgment, and that of Ashbel Green at Knopf, and he thought the two of them would merge on agreement that my little dissertation about the civil rights movement in an Alabama town should be a book.

Paul was right, at least about the consanguinity of his and Ash’s viewpoint. I had no idea at the time of how unusual this was as the fate for a dissertation. Almost thirty years later, I can say for a certainty that no subsequent book found a home so readily. Ash’s critique of my manuscript was, shall we say, lean. “Needs a new ending.” No more direction than that, and I said, all right, yes sir, and a new ending I wrote.

Over the years Ash shepherded lots of books, most bigger and more important than mine, I suspect, partly because he had good assistants (glorified secretaries, I thought at the time) who were smart and confident guys like he was. The assistant that prompted me about photos and releases and footnotes was a young man named Randall Kenan, who within a few years was a high-profile writer himself of fiction and nonfiction.

When my book won a book prize that required my attendance at the home of Ethel Kennedy one afternoon, I asked Ash if he might come along — mainly because I wanted to meet him in person, having only communicated with him through the mail. Sure enough he came (his elderly mother lived nearby, he confessed), and he quietly observed my fifteen minutes of fame.

I always wanted to publish another book with him, and we apparently were close once much later but it didn’t happen (my agent thought it was because Ash could not get the support from his paperback imprint that he needed to make a competitive offer on the advance — such were the changes in publishing in the intervening twenty-five years). I wish that we had taken less money and gone with Ash, if only because writers are sustained by such good book men as he was.

Read more about Ashbel Green from the New York Times.

Robert J. Norrell is the author of Reaping the Whirlwind: The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee, which won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award in 1986. His first work of fiction, Eden Rise, is forthcoming from NewSouth Books.

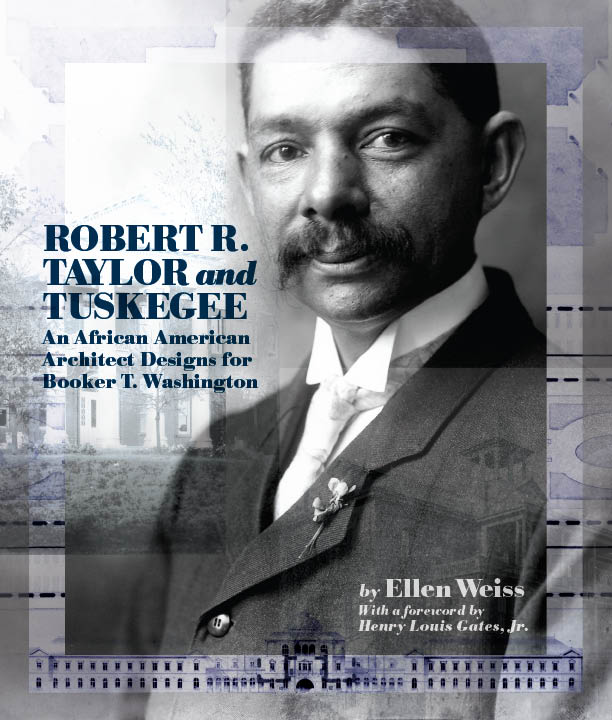

Interest in the ground-breaking African American architect Robert R. Taylor continues to grow after the publication of Professor Ellen Weiss’s detailed biography of Taylor, and articles including two in Architect magazine.

Interest in the ground-breaking African American architect Robert R. Taylor continues to grow after the publication of Professor Ellen Weiss’s detailed biography of Taylor, and articles including two in Architect magazine.